Thomas Gage

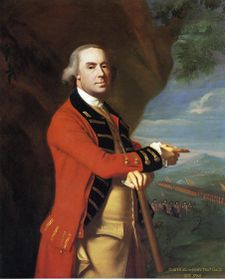

| General Thomas Gage |

|

Portrait by John Singleton Copley, circa 1768 |

|

|

Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay

|

|

| In office May 13, 1774 – October 11, 1775 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Hutchinson |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | None (John Hancock became Governor of Massachusetts in 1780) |

|

|

|

| Born | 1719 or early 1720[1] Firle, Sussex, Great Britain |

| Died | April 2, 1787 (aged 67–68) Portland Place, London, Great Britain |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret Kemble Gage |

| Profession | soldier, provincial governor |

| Religion | Anglican |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1741–1775,1781–1782 |

| Rank | full General |

| Commands | 80th Regiment of Light-Armed Foot Military governor of Montreal Commander-in-Chief, North America |

| Battles/wars | War of the Austrian Succession

|

Thomas Gage (1719 or 1720[1] – April 2, 1787) was a British general, best known for his role in the early days of the American War of Independence.

Born to an aristocratic family in England, he entered military service, seeing action in the French and Indian War, where he served alongside a future opponent, George Washington. After the fall of Montreal in 1760, he was named its military governor. During this time he did not distinguish himself militarily, but proved himself to be a competent administrator.

From 1763 to 1775 he served as commander in chief of the North American forces, including the direction of the British response to the 1763 Pontiac's Rebellion. In 1774 he was also appointed the military governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, where his actions played a role in sparking of the American War of Independence in April 1775. After his failure to resolve the Siege of Boston he was replaced by General Howe in October 1775, and returned to Britain.

Contents |

Early life

Thomas Gage was born at Firle Place, Firle, East Sussex, where the Gage family had been seated since the 15th century.[2] His father, Thomas Gage, 1st Viscount Gage, was a noted nobleman given titles in Ireland.[3] Thomas Gage (the elder) had three children, of whom Thomas was the second.[4] In 1728, Gage began attending the prestigious Westminster School where he met such figures as John Burgoyne, Richard Howe, Francis Bernard, and Lord George Sackville.[5] Despite the family's long history of Catholicism, Viscount Gage had adopted the Anglican Church in 1715,[1] and during his schoolyears Thomas became firmly attached to the church; he also likely developed the dislike for the Roman Catholic Church that became evident in later years.[6]

After graduating from Westminster in 1736 there is no record of Gage's activities[7] until he joined the British Army, eventually receiving a commission as ensign. His early duties consisted of recruiting in Yorkshire. In January 1741 he purchased a lieutenant's commission in the 1st Northampton Regiment, where he stayed until May 1742, when he transferred to Battereau's Regiment with the rank of captain-lieutenant. Gage received promotion to captain in 1743, and saw action in the War of the Austrian Succession with British forces in Flanders, where he served as aide-de-camp to the Earl of Albemarle in the Battle of Fontenoy.[8] He saw further service in the Second Jacobite Uprising, which culminated in the 1746 Battle of Culloden. From 1747 to 1748, Gage saw action under Albemarle in the Low Countries. In 1748 he purchased a Major's commission and transferred to the 55th Foot Regiment (which was later renumbered to the 44th). The regiment was stationed in Ireland from 1748 to 1755; Gage was promoted to lieutenant colonel in March 1751.[9]

During his early service years, he spent leisure time at White's Club, where he was a member, and occasionally traveled, going at least as far as Paris. He was a popular figure in the army and at the club, even though he neither liked alcohol nor gambled very much.[9] His friendships spanned class and ability. Charles Lee once wrote to Gage, "I respected your understanding, lik'd your manners and perfectly ador'd the qualities of your heart."[10] Gage also made some important political connections, forming relationships with important figures like Lord Barrington, the future Secretary at War, and Jeffrey Amherst, a man roughly his age who rose to great heights in the French and Indian War.[11]

In 1750, Gage became engaged to a "lady of rank and fortune, whom he persuaded to yield her hand in an honourable way".[12] The engagement was eventually broken, leaving Gage broken-hearted.[12] In 1753, both Gage and his father stood for seats in Parliament. Both lost in the April 1754 election, even though his father had been a Member of Parliament for some years prior. They both contested the results, but his father died soon after, and Gage withdrew his protest in early 1755, as his regiment had been sent to America following the outbreak of war there.[13]

French and Indian War

In 1755 Gage's regiment was sent to North America as part of General Braddock's expeditionary force. On this expedition Gage's regiment was in the vanguard of the troops when they came upon a company of French and Indians who were trying to set up an ambush. This skirmish began the Battle of the Monongahela, in which Braddock was mortally wounded, and George Washington distinguished himself for his courage under fire and his leadership in organizing the retreat. The commander of the 44th, Colonel Sir Peter Halkett, was one of many officers killed in the battle and Gage, who temporarily took command of the regiment, was slightly wounded.[14] The regiment was decimated, and Captain Robert Orme (General Braddock's aide-de-camp) levelled charges that poor field tactics on the part of Gage had led to the defeat. Orme resigned his army commission the following year, but as a result of his accusations Gage was denied permanent command of the 44th Regiment.[15] Gage and Washington maintained a somewhat friendly relationship for several years after the expedition, but distance and lack of frequent contact likely cooled the relationship.[16] By 1770, Washington was publicly condemning Gage's actions in asserting British authority in Massachusetts.[17]

Creation of the light infantry

In the summer of 1756 Gage served as second-in-command of a failed expedition to resupply Fort Oswego, which fell to the French while the expedition was en route.[18] The following year, he was assigned to Captain-General John Campbell Loudoun in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where a planned expedition against Louisbourg never got off the ground.[19]

In December 1757, Gage proposed to Loudoun the creation of a regiment of light infantry that would be better suited to woodland warfare. Receiving first Loudoun's approval (along with a promotion to full colonel), and later that of the war ministry, he spent the winter in New Jersey, recruiting for the newly-formed 80th Regiment of Light-Armed Foot, the "first definitely light-armed regiment in the British army."[20] While it is uncertain exactly when he met the Kembles, his choice of the Brunswick area may well have been motivated by his interest in Margaret Kemble, a well-known beauty of the area, and the granddaughter of New York Mayor Stephanus Van Cortlandt.[21] Recruiting and courtship were both successful. By February 1758 Gage was in Albany, preparing for that year's campaign, and he and Margaret were married on December 8 of that year.[22] Their first son, the future 3rd Viscount Gage, was born in 1761.

The campaign for which Gage went to Albany culminated in the disastrous Battle of Carillon, in which 16,000 British forces were defeated by barely 4,000 French forces. Gage, whose regiment was in the British vanguard, was again wounded in that battle, in which the British suffered more than 2,000 casualties.[23] Gage was then promoted to brigadier general, largely through the political maneuvering of his brother, Lord Gage.[24]

Failure to act against La Galette

The new general was placed in command of the Albany post, serving under Major General Jeffrey Amherst.[25] In 1759, shortly after capturing Ticonderoga without a fight, General Amherst learned of the death of General John Prideaux whose expedition had captured Fort Niagara. Amherst then ordered Gage to take Prideaux's place, and to take Fort de La Présentation (sometimes known as Fort La Galette) at the mouth of the Oswegatchie River on Lake Ontario. When Amherst learned that the French had also abandoned Fort St. Frédéric, he sent a messenger after Gage with more explicit instructions to capture La Galette and then, if at all possible, to advance on Montreal.[26]

When Gage arrived at Oswego, which had been captured in July by troops under Frederick Haldimand's command, he surveyed the situation, and decided that it was not prudent to move against La Galette. Expected reinforcements from Fort Duquesne had not arrived, the French military strength at La Galette was unknown, and its strength near Montreal was believed to be relatively high. Gage, believing an attack on La Galette would not gain any significant advantage, decided against action, and sent Amherst a message outlining his reasons.[27] Although Amherst was incensed at Gage's failure, and there was no immediate censure from either Amherst or the war ministry, Gage's troops were in the rear of Amherst's army in the 1760 expedition that resulted in Montreal's surrender.[28]

Early Governorship

After the French surrender, Amherst named Gage the military governor of Montreal, a task Gage found somewhat thankless, as it involved the minute details of municipal governance along with the administration of the military occupation. He was also forced to deal with civil litigation, and manage trade with the Indians in the Great Lakes region, where traders disputed territorial claims, and quarreled with the Indians.[29] Margaret came to stay with him in Montreal, and that is where his first two children, Harry and Maria Theresa, where born.[30] In 1761, he was promoted to major general, and in 1762, again with the assistance of his brother, was placed in command of the 22nd Regiment, which assured a command even in peacetime.[31]

By all accounts, Gage appeared to be a fair administrator, respecting people's lives and property, although he had a healthy distrust of the landowning seigneurs and of the Roman Catholic clergy, who he viewed as intriguers for the French. When peace was announced following the 1763 Treaty of Paris, Gage began lobbying for another posting, as he was "very much [tired] of this cursed Climate, and I must be bribed very high to stay here any longer".[28] In October 1763 the good news arrived that he would act as commander-in-chief of North America while Amherst was on leave in England. He immediately left Montreal, and took over Amherst's command in New York on November 17, 1763. When he did so, he inherited the job of dealing with the Indian uprising known as Pontiac's Rebellion.[32]

Pontiac's Rebellion

In May 1763 Ottawa leader Pontiac, unhappy with the terms of the Treaty of Paris and British plans for administration of the formerly French territories, launched a series of attacks on British frontier forts, successfully driving the British from some, threatening others, and also terrorizing the settlers in those areas.[33]

Hoping to end the conflict diplomatically, Gage ordered Colonel John Bradstreet and Colonel Henry Bouquet out on military expeditions and also ordered Sir William Johnson to engage in peace negotiations.[35] Johnson negotiated the Treaty of Fort Niagara in the summer of 1764 with some of the disaffected tribes, and Colonel Bouquet negotiated a cease-fire of sorts in October 1764, which resulted in another peace treaty negotiated by Johnson in 1765. In 1765, the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment finally got through to Fort Cavendish, the last fort still in French hands. The conflict was not fully resolved until Pontiac himself travelled to Fort Ontario and signed a formal treaty with Johnson in July 1766.

Securing his position

When General Amherst left North America in 1763, it was on a leave of absence from his position as commander-in-chief. In 1764, Amherst announced that he had no intention of returning to North America, at which point Gage's appointment to that post was made permanent. (Amherst retained posts as governor of Virginia and colonel of the 60th Foot, positions he only gave up in 1768 when he was required to actually go to Virginia or give up the post.)[36] Intrigues of other high-ranking officers, especially Robert Monckton and his supporters, for his offices, continued throughout his tenure as commander-in-chief. Gage was promoted to lieutenant general in 1771.[37] In 1767 Gage ordered the arrest of Major Robert Rogers, the former leader of Rogers' Rangers who Gage had come to dislike and distrust during the war. The arrest was based on flimsy evidence that Rogers might have been engaging in a treasonous relationship with the French; he was acquitted in a 1768 court martial.

Gage spent most of his time as commander-in-chief, the most powerful office in British America, in and around New York City.[38] While Gage was burdened by the administrative demands of managing a territory that spanned the entirety of North America east of the Mississippi River, the Gages clearly relished life in New York, actively participating in the social scene.[39] Although his position gave him the opportunity to engage in financial arrangements that gave high-ranking officers the opportunity to line their pockets at the expense of the military purse, there is little evidence that he engaged in any significant improper transactions. In addition to the handsome sum of £10 per day as commander-in-chief, he received a variety of other stipends, including his colonel's salary, given for leading his regiment. These funds made it possible to send all of the Gage children (at least six of whom survived to adulthood) to school in England.[40]

If Gage did not dip his hand unnecessarily in the public till, he did engage in the relatively common practices of nepotism and political favoritism. In addition to securing advantageous positions for several people named Gage or Kemble, he also apparently assisted in the placement of some of his friends and political supporters, or their children.[41]

Rising colonial tension

During Gage's administration political tensions rose throughout the American colonies. As a result, Gage began withdrawing troops from the frontier to fortify urban centers like New York City and Boston. As the number of soldiers stationed in cities grew, the need to provide adequate food and housing for these troops became urgent. Parliament passed the Quartering Act of 1765, permitting British troops to be quartered in private residences. Gage personally traveled to Boston and spent six weeks there making quartering arrangements for the new soldiers in 1768. The military occupation of Boston eventually led to the Boston Massacre of 1770. That same year, Gage was promoted to lieutenant general. Late that year he wrote "America is a mere bully, from one end to the other, and the Bostonians by far the greatest bullies."[42]

Governor of Massachusetts

Gage returned to England in June 1773 with his family and thus missed the Boston Tea Party in December of that year. The British Parliament passed a series of measures known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts as a way to punish the colonies, and specifically the Province of Massachusetts Bay, for this and other acts of protest against British colonial policy.

Massachusetts governor Thomas Hutchinson was 62 years old at the time and the lieutenant governor (Andrew Oliver), a hated Tory, was 67. Still in his early 50s and with significant military experience in America, Gage was deemed the best man to handle the brewing crisis, and to enforce the Parliamentary acts.

In early 1774, he was appointed military Royal governor, or commander-in-chief, of Massachusetts, replacing the civilian governor Thomas Hutchinson. He arrived from England in early May, first stopping at Castle William on Castle Island in Boston Harbor. He then arrived in Boston on May 13, 1774, having been carried there by the HMS Lively. His arrival was met with little pomp and circumstance, but was generally well received at first as Bostonians were happy to see Hutchinson go.[43] In that capacity, he was entrusted with carrying into effect the Boston Port Act and the Massachusetts Government Act. General Gage also sought to strictly enforce the confiscation of war-making materials.

In September 1774, he ordered a mission to remove provincial gunpowder from a magazine in what is now Somerville, Massachusetts.[44] This action, while successful, caused a huge popular reaction known as the Powder Alarm that prevented Gage from successfully executing other raids. This was in large part due to Paul Revere and the Sons of Liberty. The Sons of Liberty kept careful watch over Gage's activities after this point and successfully warned others of future actions before Gage could mobilise his British regulars to execute them.

Gage found himself criticized by his own men for allowing groups like the Sons of Liberty to exist. One of his officers, Hugh Percy remarked, "The general's great lenity and moderation serve only to make them (the Americans) more daring and insolent." Gage himself wrote, "If force is to be used at length, it must be a considerable one, and foreign troops must be hired, for to begin with small numbers will encourage resistance, and not terrify; and will in the end cost more blood and treasure." Edmund Burke described Gage's conflicted relationship by saying in Parliament, "An Englishman is the unfittest person on Earth to argue another Englishman into slavery."

American War of Independence

At Concord, on the night of April 18, 1775, Gage ordered 700 British regulars from elite flank companies (Light Infantry and Grenadiers) to march from Boston to Concord to confiscate military supplies the colonists had stored there.[45] A brief skirmish in Lexington scattered colonial militia forces gathered there, but in a later standoff in Concord, a portion of the British force was routed by a stronger colonial militia contingent. When the British left Concord following their search (which was largely unsuccessful, as the colonists, with advance warning of the action, had removed most of the supplies), arriving colonial militia engaged the British column in a running battle all the way back to Charlestown.

The Battles of Lexington and Concord resulted in 273 total casualties for the British and 95 for the American rebels. In June, Gage issued a proclamation granting a general pardon to all who would demonstrate loyalty to the crown—with the notable exceptions of Hancock and Adams.

Following Lexington, the American colonists followed the British back to Boston, and surrounded the city, beginning the Siege of Boston. Initially, the 6,000 to 8,000 rebels (led mainly by General Artemas Ward) faced some 4,000 of General Gage’s British regulars, bottled up in the city. British Admiral Samuel Graves commanded the fleet that continued to control the harbour. On May 25, Gage received about 4,500 reinforcements and three new Generals - Major General William Howe and Brigadiers John Burgoyne and Henry Clinton.

Gage started work with his new generals on a plan to break the grip of the besieging forces. They would use an amphibious assault to take control of the unoccupied Dorchester Heights and eventually take the colonial headquarters at Cambridge. When the colonists received word of these plans, General Ward gave orders to General Israel Putnam to fortify Bunker Hill. On June 17, 1775, British forces under General Howe seized the Charlestown peninsula at the Battle of Bunker Hill. They did take their objective, but didn't break out because the Americans held the ground at the base of the peninsula. Gage called it, "A dear bought victory, another such would have ruined us." British losses were so heavy that from this point, the siege essentially became a stalemate. One political effect of the battle was the British decision to recall Gage. The siege ended in March 1776 when the colonists fortified the Dorchester Heights, prompting the British forces to evacuate the city.

Return to Britain

On June 25, 1775, Thomas Gage wrote a dispatch to Britain, notifying Lord Dartmouth of the results of the June 17 battle.[46] Three days after his report arrived in England, Dartmouth issued the order recalling Gage and replacing him with William Howe.[47] The rapidity of this action is likely attributable to the fact that people within the government were already arguing for Gage's removal, and the battle was just the final straw.[48] Gage received the order in Boston on September 26,[49] and set sail for England on October 11.[50]

The nature of Dartmouth's recall did not actually strip Gage of his offices. William Howe temporarily replaced him as commander of the forces in Boston, while General Guy Carleton was given command of the forces in Quebec.[50] Although King George wanted to reward his "mild general" for his service, Gage's sole reward after Lord Germain (who succeeded Dartmouth as the Secretary of State for North America) formally gave his command to Howe in April 1776 was that he retained the governorship of Massachusetts.[51]

On the Gage's return to England, they eventually settled into a house on Portland Place in London. While he was presumably given a friendly reception in his interview with a sympathetic King George,[50] the public and private writings about him and his fall from power were at times vicious. One correspondent wrote that Gage had "run his race of glory ... damn him! let him alone to the hell of his own conscience and the infamy which must inevitably attend him!"[51] Others were kinder; New Hampshire Governor Benning Wentworth characterized him as "a good and wise man ... surrounded by difficulties."[51]

Gage was briefly reactivated to duty in April 1781, when Amherst appointed him to mobilize troops for a possible French invasion.[52] The next year, Gage assumed command (as a colonel) of the 17th Light Dragoons. He was finally promoted to full general on November 20, 1782, and later transferred to command the 11th Dragoons, though he was recognized as a general months in advance.

Final years and legacy

As the war machinery was reduced in the mid-1780s, Gage's military activities declined. He supported the efforts of Loyalists to recover losses incurred when they were forced to leave the colonies, notably confirming the treachery of Benjamin Church in order to further his widow's claims for compensation.[53] He received visitors at Portland Place and at Firle, including Frederick Haldimand and Thomas Hutchinson.[54] His health began to decline early in the 1780s.[53]

Gage died at Portland Place on April 2, 1787, and was buried in the family plot at Firle.[55] His wife survived him by almost 37 years.[56] His son Henry inherited the family title upon the death of Gage's brother William, and became one of the wealthiest men in England.[57] His youngest son, William Hall Gage, became an admiral in the Royal Navy, and all three daughters married into well-known families.[58] His second son, also named Thomas, went on to achieve modest fame in the field of botany. A descendant of Gage was Field Marshal John Vereker, 6th Viscount Gort VC, who served as Chief of the Imperial staff.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Hinman (2002), p. 8

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 2

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 6

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 8

- ↑ Alden (1948), pp. 9–10

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 10

- ↑ Hinman (2002), p. 10

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 13

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Alden (1948), p. 14

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 15

- ↑ Alden (1948), pp. 15–16

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Alden (1948), p. 16

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 17

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 25

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 26

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 29

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 30

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 37

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 40

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 48

- ↑ Alden (1948), pp. 43–44

- ↑ Alden (1948), pp. 44,46

- ↑ Twatio, p.4

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 46

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 47

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 49

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 50

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Wise

- ↑ Alden (1948), pp. 55–58

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 59

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 60

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 61

- ↑ Alden (1948), pp. 89–91

- ↑ Dowd (2002), p. 6

- ↑ Alden (1948), pp. 94,97

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 63

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 64

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 65

- ↑ Alden (1948), pp. 66–72

- ↑ Alden (1948), pp. 68–69

- ↑ Alden (1948), pp. 73–75

- ↑ National Geographic Society (1997). Exploring America's Historic Places. National Geographic Society.

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 204

- ↑ Fischer, pp. 44–45

- ↑ Fischer, p. 85

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 270

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 280

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 281

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 278

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Alden (1948), p. 283

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Alden (1948), p. 284

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 291

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Alden (1948), p. 292

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 287

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 293

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 294

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 289

- ↑ Alden (1948), p. 288

References

- Alden, John R (1948). General Gage in America. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780837122649. OCLC 181362.

- Dowd, Gregory Evans (2002). War under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, & the British Empire. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7079-8. ISBN 0-8018-7892-6 (paperback).

- Fischer, David Hackett (1995). Paul Revere's Ride. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509831-5.

- Hinman, Bonnie (2002). Thomas Gage: British General. Philadelphia: Chelsea House. ISBN 0-7910-6385-2 (paperback).

- Bill Twatio (August, 2006). "The battle at Fort Carillon: "what a day for France! What soldiers are ours!" Montcalm marvelled as he raised a great cross to celebrate a victory "wrought by God."". Esprit de Corps. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_6972/is_8_13/ai_n28376711/pg_4/?tag=content;col1.

- Wise, S.F.. "Thomas Gage biography". Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=1895. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Gage Papers at the University of Michigan Clements Library

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- Haldimand Collection (Papers)

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Lord Amherst |

Commander-in-Chief, North America 1763–1775 |

Succeeded by William Howe |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Thomas Hutchinson |

Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay May 13, 1774 – October 11, 1775 |

Succeeded by John Hancock (as Governor of Massachusetts in 1780) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||